Kimchi Premium vs. State Hackers: The Hidden North-South Korea Cyberwar Following Multiple Upbit Breaches

The market is rebounding, but exchanges are once again facing security breaches.

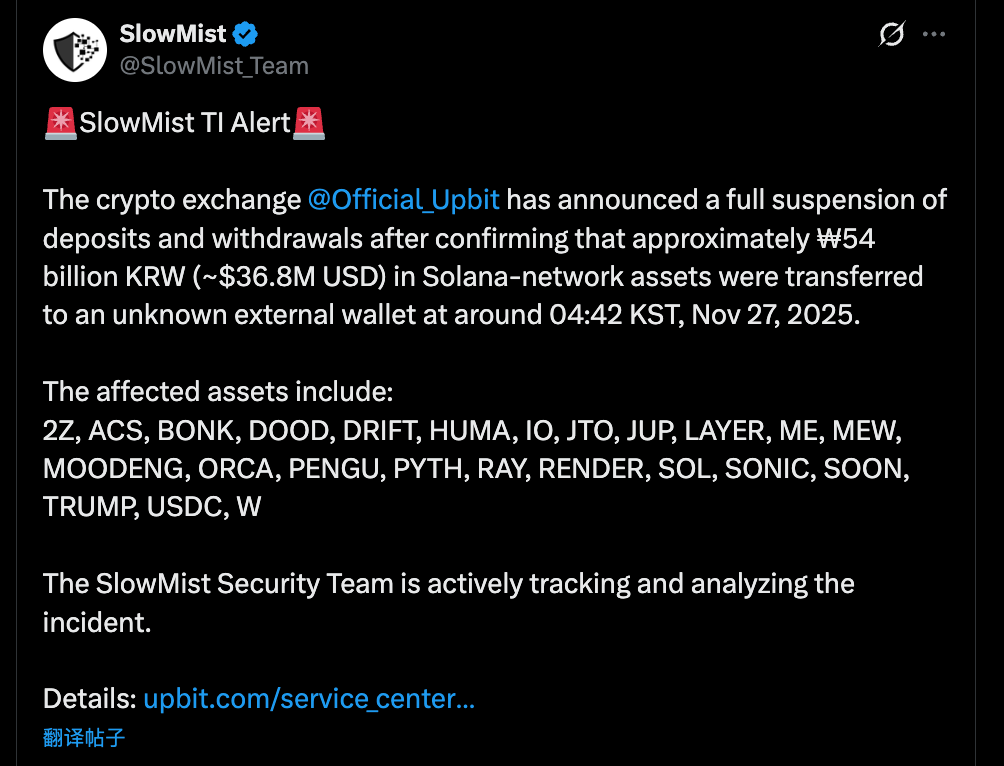

On November 27, Upbit—South Korea’s largest cryptocurrency exchange—confirmed a major security incident that resulted in the loss of approximately KRW 54 billion (USD 36.8 million) in assets.

At 4:42 AM KST on November 27, while most Korean traders were still asleep, Upbit’s Solana hot wallet saw an unusually large outflow of funds.

Blockchain security firms such as SlowMist reported that the attacker did not target a single asset. Instead, they executed a sweeping theft of Upbit’s holdings on the Solana network.

The stolen assets included core tokens like SOL and USDC, as well as nearly all major SPL tokens within the Solana ecosystem.

Partial list of stolen assets:

- DeFi/Infrastructure: JUP (Jupiter), RAY (Raydium), PYTH (Pyth Network), JTO (Jito), RENDER, IO, and others.

- Meme/Community: BONK, WIF, MOODENG, PENGU, MEW, TRUMP, and others.

- Other projects: ACS, DRIFT, ZETA, SONIC, and others.

This comprehensive theft suggests the attacker likely gained access to Upbit’s Solana hot wallet private key, or compromised the signing server, enabling authorization and transfer of all SPL tokens held in the wallet.

For Upbit, which controls 80% of South Korea’s crypto market and boasts the highest security certification from the Korea Internet & Security Agency (KISA), this is a devastating breach.

But this isn’t the first time a South Korean exchange has been hacked.

Looking at the broader timeline, the South Korean crypto market has been a consistent target for hackers—especially from North Korea—over the past eight years.

South Korea’s crypto market is not only a hotspot for retail speculation, but also a favored “ATM” for North Korean hackers.

Eight Years of North-South Cyber Conflict: A Chronicle of Exchange Breaches

Attack techniques have evolved from brute-force hacks to sophisticated social engineering, and the list of South Korean exchanges targeted has only grown longer.

Total losses: About KRW 200 million (USD 200 million at the time of theft; over USD 1.2 billion at current values, with the 342,000 ETH stolen from Upbit in 2019 now worth more than USD 1 billion)

- 2017: The Wild West—Hackers Target Employee Computers

2017 marked the beginning of the crypto bull market and the start of a nightmare for South Korean exchanges.

Bithumb, the largest exchange in South Korea, was the first major victim. In June, hackers breached a Bithumb employee’s personal computer, stealing the personal data of about 31,000 users. Using this information, they executed targeted phishing attacks and stole roughly KRW 32 million (USD 32 million). Investigators found that unencrypted customer data was stored on the employee’s device, and basic security updates were missing.

This incident revealed gaps in security management at South Korean exchanges at the time—even basic rules like not storing customer data on personal computers were absent.

The collapse of mid-sized exchange Youbit was even more significant. Over one year, Youbit suffered two catastrophic hacks: nearly 4,000 BTC (about KRW 5 million or USD 5 million) lost in April, and another 17% of assets stolen in December. Unable to recover, Youbit declared bankruptcy, allowing users to withdraw only 75% of their balances, with the rest subject to lengthy bankruptcy proceedings.

After the Youbit incident, KISA publicly accused North Korea of orchestrating the attack for the first time, sending a clear signal to the market:

Exchanges were now facing nation-state hacker groups with geopolitical motives, not just ordinary cybercriminals.

- 2018: The Hot Wallet Heist

June 2018 saw a string of attacks on the South Korean market.

On June 10, mid-sized exchange Coinrail was breached, losing over KRW 40 million (USD 40 million). Unlike previous incidents, hackers mainly targeted ICO tokens (like NPXS from Pundi X), not Bitcoin or Ethereum. The news triggered a brief Bitcoin price drop of more than 10%, and the crypto market lost over USD 4 billion in value within two days.

Just ten days later, top exchange Bithumb was hacked, losing about KRW 31 million (USD 31 million) in XRP and other tokens from its hot wallet. Ironically, just days before, Bithumb had announced on Twitter it was “transferring assets to cold wallets to upgrade its security system.”

This was Bithumb’s third hack in eighteen months.

The series of breaches severely damaged market confidence. The Ministry of Science and ICT audited 21 domestic exchanges, finding only 7 passed all 85 security checks. The remaining 14 were “at constant risk of hacking,” with 12 showing major cold wallet management flaws.

- 2019: Upbit’s 342,000 ETH Theft

On November 27, 2019, Upbit suffered South Korea’s largest single crypto theft.

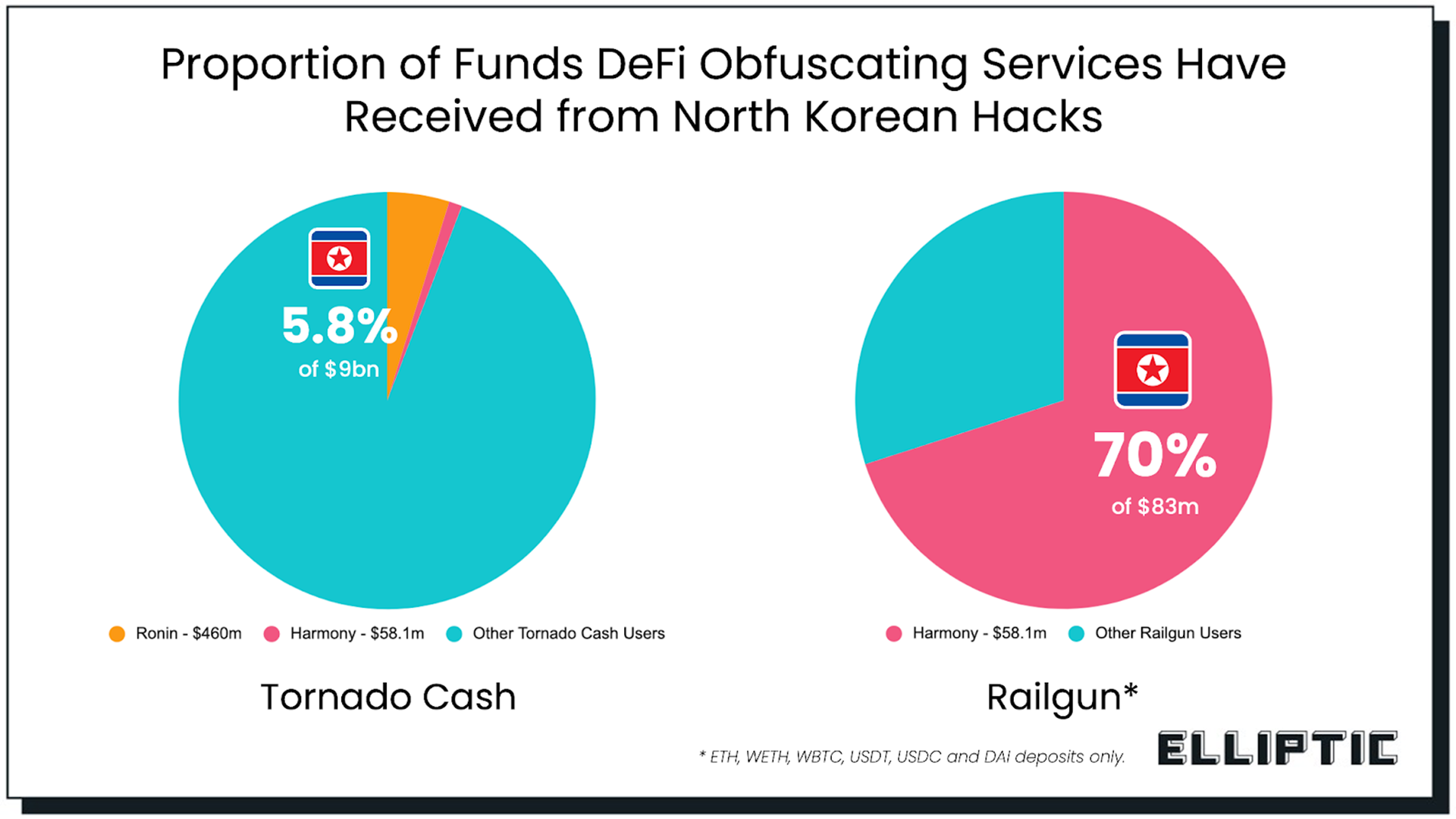

Hackers exploited a wallet consolidation process to transfer 342,000 ETH in one transaction. Instead of dumping the assets, they used “peel chain” techniques to split the funds into countless small transactions, layering transfers through dozens of exchanges without KYC requirements and mixers.

Investigators found that 57% of the stolen ETH was exchanged for Bitcoin at a 2.5% discount on exchanges suspected to be operated by North Korea, while the remaining 43% was laundered via 51 exchanges in 13 countries.

It was not until November 2024—five years later—that South Korean police officially confirmed the attack was carried out by North Korea’s Lazarus Group and Andariel. Investigators traced IP addresses, analyzed fund flows, and found North Korean-specific code words like “흘한 일” (“not important”) in the attack software.

South Korean authorities, working with the FBI, spent four years tracking the assets, eventually recovering 4.8 BTC (about KRW 600 million) from a Swiss exchange and returning it to Upbit in October 2024.

Compared to the total stolen, this recovery is negligible.

- 2023: The GDAC Incident

On April 9, 2023, mid-sized exchange GDAC was hacked, losing about KRW 13 million (USD 13 million)—23% of total assets under custody.

The stolen assets included around 61 BTC, 350 ETH, 10 million WEMIX tokens, and 220,000 USDT. Hackers seized GDAC’s hot wallet and quickly laundered part of the funds through Tornado Cash.

- 2025: Upbit Breached Again—Six Years to the Day

On November 27, six years after its previous breach, Upbit suffered another major theft.

At 4:42 AM, Upbit’s Solana hot wallet saw abnormal outflows, with about KRW 54 billion (USD 36.8 million) transferred to unknown addresses.

Following the 2019 Upbit hack, South Korea introduced the Special Act in 2020, mandating ISMS certification and real-name bank accounts for all exchanges. Many smaller exchanges exited the market, leaving a handful of giants. Upbit, backed by Kakao and certified, captured over 80% market share.

Despite six years of regulatory reform, Upbit was not immune to another attack.

As of publication, Upbit has pledged to fully compensate affected users, but details on the attacker and method remain undisclosed.

“Kimchi Premium,” State-Sponsored Hackers, and Nuclear Weapons

Frequent security incidents at South Korean exchanges are not simply technical failures—they reflect the tragic realities of geopolitics.

In a highly centralized, liquidity-rich, and geographically unique market, South Korean exchanges are forced to defend themselves with commercial security budgets against nation-state hacker units with nuclear ambitions.

This unit is known as the Lazarus Group.

Lazarus operates under North Korea’s Reconnaissance General Bureau (RGB) and is one of Pyongyang’s most elite cyber warfare teams.

Before targeting crypto, Lazarus had already demonstrated its capabilities in traditional finance.

They breached Sony Pictures in 2014, stole KRW 81 million (USD 81 million) from the Bank of Bangladesh in 2016, and launched the WannaCry ransomware attack in 2017, impacting 150 countries.

Starting in 2017, Lazarus shifted its focus to cryptocurrencies for a simple reason:

Crypto exchanges are less regulated, have inconsistent security standards, and stolen funds can be rapidly transferred cross-border on-chain, bypassing international sanctions.

South Korea is an ideal target.

First, it’s a natural geopolitical rival. Attacking South Korean businesses provides North Korea with both funds and chaos in an “enemy” state.

Second, the “kimchi premium” creates a lucrative liquidity pool. South Korean retail investors are famously enthusiastic, driving up demand and creating persistent premiums as KRW chases limited crypto assets.

This means South Korean exchanges’ hot wallets hold far more liquidity than those in other markets—a gold mine for hackers.

Third, language is an advantage. Lazarus excels at social engineering—fake job postings, phishing emails, impersonating customer service to obtain verification codes.

With no language barrier, targeted phishing attacks on South Korean employees and users are much more effective.

Where do the stolen funds go? That’s perhaps the most critical part of the story.

UN reports and blockchain analytics firms have traced Lazarus’s stolen crypto to North Korea’s nuclear and missile programs.

Previously, Reuters cited a confidential UN report showing North Korea uses stolen cryptocurrency to help fund missile development.

In May 2023, White House Deputy National Security Advisor Anne Neuberger stated that roughly 50% of North Korea’s missile program funding comes from cyberattacks and crypto theft, up from “about a third” in July 2022.

Simply put, every South Korean exchange hack may be indirectly supporting nuclear warhead development across the DMZ.

The money laundering process is now highly sophisticated: assets are split into numerous small transactions using “peel chain” techniques, mixed via Tornado Cash or Sinbad, exchanged for Bitcoin at a discount on North Korean-run exchanges, and finally converted to fiat through underground channels in China and Russia.

For the 342,000 ETH stolen from Upbit in 2019, South Korean police reported that 57% was exchanged for Bitcoin at three North Korean-operated exchanges at a 2.5% discount, with the remaining 43% laundered through 51 exchanges in 13 countries. Most funds remain unrecovered years later.

This highlights the core dilemma facing South Korean exchanges:

On one side, Lazarus boasts state resources, unlimited investment, and 24/7 operations. On the other, commercial firms like Upbit and Bithumb must defend against relentless, state-sponsored threats.

Even top exchanges with robust security audits struggle against persistent nation-state attacks.

This Isn’t Just South Korea’s Problem

Eight years, more than a dozen attacks, and KRW 200 million (USD 200 million) in losses—if you see this as only a local South Korean issue, you’re missing the bigger picture.

South Korean exchanges’ experience is a preview of the crypto industry’s struggle against nation-state adversaries.

North Korea is the most notorious, but not the only player. Russian threat groups have been linked to DeFi attacks; Iranian hackers have targeted Israeli crypto firms; and North Korea has expanded its reach globally, as seen in the USD 1.5 billion Bybit hack in 2025 and the USD 625 million Ronin breach in 2022, impacting victims worldwide.

The crypto industry faces a fundamental challenge: everything flows through centralized gateways.

No matter how secure the blockchain, assets ultimately pass through exchanges, bridges, and hot wallets—prime targets for attackers.

These nodes concentrate vast sums but are managed by commercial firms with limited resources, making them ideal hunting grounds for state-sponsored hackers.

Defender and attacker resources are fundamentally unequal. Lazarus can fail a hundred times; an exchange can only fail once.

The “kimchi premium” will continue to attract global arbitrageurs and local retail investors. Lazarus won’t stop just because it’s exposed, and the battle between South Korean exchanges and nation-state hackers is far from over.

Let’s hope the next stolen funds aren’t yours.

Statement:

- This article is republished from [TechFlow]. Copyright belongs to the original author [TechFlow]. For any concerns regarding republication, please contact the Gate Learn team for prompt handling according to established procedures.

- Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not constitute investment advice.

- Other language versions are translated by the Gate Learn team. Unless Gate is cited, translated articles may not be copied, distributed, or plagiarized.

Related Articles

The Future of Cross-Chain Bridges: Full-Chain Interoperability Becomes Inevitable, Liquidity Bridges Will Decline

Solana Need L2s And Appchains?

Sui: How are users leveraging its speed, security, & scalability?

Navigating the Zero Knowledge Landscape

What is Tronscan and How Can You Use it in 2025?